territorio padovano

Padova città

Colli Euganei

fotografie panoramiche

Terme Euganee e area termale

Padova città d'acque

Cittadella e cittadellese Camposampiero Piazzola sul Brenta Curtarolo Monselice Este e l'estense Montagnana e la Sculdascia Conselve e conselvano Piove di Sacco, Saccisica

musei padovani chiese padovane ville venete castelli padovani Comuni padovani

Cittadella e cittadellese Camposampiero Piazzola sul Brenta Curtarolo Monselice Este e l'estense Montagnana e la Sculdascia Conselve e conselvano Piove di Sacco, Saccisica

musei padovani chiese padovane ville venete castelli padovani Comuni padovani

cicloturismo mountain bike

nella pianura veneta

Treviso marca trevigiana Venezia e terraferma Vicenza e vicentino Rovigo e Polesine

nella pianura veneta

Treviso marca trevigiana Venezia e terraferma Vicenza e vicentino Rovigo e Polesine

news eventi mercatini

showcase, vetrina

agricoltura, agriturismo

aree ricreative giochi, pic-nic

Comuni, paesi e città

meteorologia, web-cams

città di Padova, Padoua, Padoue

Padova città d'arte e di tradizioni mitologiche

Padova città d'arte e di tradizioni mitologiche

Vedere, conoscere, fotografare la città di Padova: Sant'Antonio da Padova, Santa Giustina, Prato della Valle, Palazzo Ragione, Cappella degli Scrovegni

Basilica di Sant'Antonio, il 'Santo'

- la Basilica di Sant'Antonio a Padova, 'il Santo'

- Padova: Basilica di Sant'Antonio - foto panoramica (1)

- Padova: Basilica di Sant'Antonio - foto panoramica (2)

- Padova: Basilica di Sant'Antonio - foto panoramica (3)

Basilica di Santa Giustina e Prato della Valle

- Basilica di Santa Giustina e Prato della Valle

- l'Orto Botanico universitario

- Prato della Valle, Isola Memmia e Basilica di Santa Giustina

- panoramica sul Prato della Valle

- panoramica sul Prato della Valle e la Basilica di Santa Giustina (1)

- panoramica sul Prato della Valle e la Basilica di Santa Giustina (2)

- panoramica sul Prato della Valle e la Basilica di Santa Giustina (3)

- Prato della Valle e Basilica di Santa Giustana - panoramica (1)

- Isola Memmia, Prato della Valle e Basilica di Santa Giustana - panoramica (2)

- Isola Memmia, Prato della Valle - panoramica (3)

- Isola Memmia, Prato della Valle - panoramica (4)

- i notabili di Prato della Valle, statue dell'Isola Memmia

piazza Duomo, Battistero e ex Ghetto Ebraico

- Cattedrale Duomo e Battistero, Reggia dei Carraresi

- piazza Duomo ed il Battistero - panoramica (1)

- piazza Duomo ed il Battistero - panoramica (2)

- l'ex Ghetto Ebraico di Padova

le Piazze: piazza Erbe Frutta, piazza Signori, palazzo del Bo, Caffè Pedrocchi, palazzo della Ragione

- Palazzo della Ragione, piazza delle Erbe piazza della Frutta, piazza municipio

- Piazza dei Signori, torre dell'Orologio e Reggia Carrarese

- Padova: torre dell'Orologio - foto panoramica

- Padova: piazza dei Signori, palazzo del Capitano e torre dell'Orologio - panoramica

- Piazza dei Signori, torre dell'Orologio - panoramica

- il caffè Pedrocchi

- caffè Pedrocchi, palazzo del Bo, piazza del Municipio - panoramica

Chiesa agli Eremitani e Cappella degli Scrovegni

- Chiesa degli Eremitani, Cappella Ovetari, musei agli Eremitani e Cappella degli Scrovegni

- piazza e chiesa agli Eremitani - panoramica

- Arena romana e Cappella degli Scrovegni - panoramica (1)

- Arena romana e Cappella degli Scrovegni - panoramica (2)

il Castello Medioevale, la Torlonga o torre della Specola, i luoghi ezzeliniani

- Torlonga, Castelvecchio o Castello di Ezzelino e la Specola di Galileo Galilei

- Torre della Specola o Torlonga del Castelvecchio (o di Ezzelino) - foto panoramica

la Padova veneziana: bastioni, mura veneziane e porte cinquecentesche

- Padova, le mura veneziane e le cinquecentesche porte monumentali

- il Bastione Impossibile delle mura veneziane - foto panoramica

- Bastione Santa Croce delle mura veneziane

- la porta Santa Croce delle mura veneziane - foto panoramica

Padova città d'acque

- i canali fluviali di Padova e provincia

- Padova città d'acque e argini ciclabili

- lungo il Canale Scaricatore a Padova - panoramica

- il Canale Scaricatore al sostegno di Ca'Nordio a Padova - panoramica

- lungo il Canale San Gregorio - panoramica

- voga alla veneta sul Piovego, Portello, Porte Contarine - fotografie

- ciclovia Valsugana-Brenta: Trento, Bassano, Padova, Venezia

chiese e palazzi vari

- Chiesa di Santa Sofia

- Scuola della Carità di via San Francesco

- Padova: chiesa di San Nicolò - foto panoramica

- corso Umberto I e palazzo Emo-Capodilista - foto panoramica

- chiesetta campestre di Pozzoveggiani a Salboro

approfondimenti

- cronache Ezzeliniane: la storia degli Ezzelini dal 1000 al 1260

- cronache Carraresi: la Padova del '300

- Lega di Cambrai e guerra anti-veneziana

Padova città d'arte e di tradizioni mitologiche - tra storia e leggenda

Padova città d'arte e di tradizioni mitologiche - tra storia e leggenda

Padova vanta origini remote di città fluviale. Un'antica leggenda narra che la città sia stata fondata da Antenore, eroe omerico in fuga da Troia data alle fiamme. Testimonianze archeologiche confermano l'esistenza, intorno al XII secolo a.C., di un insediamento urbano in una zona acquitrinosa formatasi per la presenza del fiume Brenta, chiamato a quel tempo "Medoacus". Lo stesso toponimo "Patavium", da cui Padova, sarebbe riferibile a Padus ed indicherebbe uno stretto rapporto tra l'insediamento paleoveneto e le acque fluviali. E Piazza Antenore conserva ancor oggi le spoglia del mitico fondatore, proprio accanto alle arcate di uno dei ponti romani, ora interrati, che attraversavano il Naviglio interno alla città: la più importante via d'acqua che permetteva di raggiungere la laguna.Già nel III secolo a.C. Padova, grazie alla sua posizione ideale di città protetta dalle acque, sconfigge i Galli Cisalpini e diviene preziosa alleata di Roma. Intorno al 50 a.C. essa possiede una propria autonomia amministrativa avendo acquisito dapprima lo stato di jus romano e successivamente quello di Municipium per decreto di Giulio Cesare. La prosperità e la pace raggiunte portano ad un riassetto urbanistico e ad un immane sforzo di regolamentazione delle acque del fiume con la costruzione dei ponti di epoca romana. Ecco allora che Padova può dirsi "un'isola", le cui fortificazioni naturali sono le anse del fiume, collegata al contado tramite il graticolato delle strade romane ed unita al mare attraverso i suoi canali navigabili.

Le più importanti costruzioni di età romana sono il teatro, che determina l'attuale conformazione ad anello del Prato della Valle, e l'anfiteatro di cui restano tracce lungo il Corso del Popolo e al cui interno è oggi situata la Cappella degli Scrovegni. Tuttavia l'abitudine di demolire gli edifici più antichi per il riuso delle pietre da costruzione, assai difficili da reperire, ha determinato la scarsità di testimonianze architettoniche di quell'epoca. Con l'intervento romano (II-I sec. a.C.) la città diventa poi uno dei nodi viari più importanti del Nord: la via Aemilia la collega ad Aquileia, la via Aemilia-Gallica la conduce a Vicenza e da lì a Genova, la Annia la unisce all'importante porto di Adria.

Se durante i primi secoli del cristianesimo Padova è fra le città più importanti dell'impero, seconda solo a Roma in ricchezza e bellezza, dal III-IV sec. inizia a decadere a causa delle irruzioni via via più frequenti di Visigoti, Svevi e Vandali prima, Unni e Longobardi poi.

Nel 589 si verifica un evento drammatico: il fiume Brenta, rimasto ormai da un secolo senza significativi interventi idraulici, tracima e provoca una serie di devastanti inondazioni. Il suo corso devia a nord e il Bacchiglione ne occupa il sito. La popolazione fugge in massa trovando riparo nella campagna circostante e in laguna. Nel 602 la città è infine letteralmente rasa al suolo dai Longobardi dopo un assedio durato ben tredici anni. Segue un lungo periodo di abbandono caratterizzato da miseria, instabilità politica e mancanza di punti fermi in campo religioso.

La ripresa è molto lenta e faticosa e si dovrà attendere addirittura il XII sec. perché Padova diventi un libero comune e cominci a riaffermare la sua supremazia imponendo al contado e alle città vicine il proprio modello culturale. Il recupero urbanistico-territoriale è possibile in primo luogo per l'opera dei monaci benedettini che iniziano dall'VIII sec. una capillare bonifica partendo da Padova per arrivare alla Pedemontana. L'azione dei monaci è presto detta: una volta individuato il sito adeguato per la costruzione di un nuovo monastero si edifica il complesso, si innalzano mulini lungo i corsi d'acqua e si dà inizio al risanamento del terreno. Ai monaci si deve anche l'importantissimo recupero della centuriazione romana e la diffusione di un nuovo tipo di edificio rurale, forgiato sul monastero benedettino.

Intorno al 1200 Padova ritrova la ricchezza economica e vive un periodo di grosso fervore culturale: viene costruita la prima cerchia di mura medioevali, sono edificate numerose fabbriche fra le quali la Basilica del Santo e il Palazzo della Ragione, viene fondata una prestigiosa Università. La scena artistica è dominata da una figura di assoluto prestigio: il fiorentino Giotto, autore di una vera e propria rivoluzione della pittura. A lui è affidata la decorazione ad affresco della Cappella degli Scrovegni. L'apice della potenza politica è raggiunto tra il 1338 e il 1405 con la signoria dei Carraresi.

L'anno 1405 segna una battuta d'arresto perché una rivolta popolare consegna la città nelle mani della Repubblica di Venezia. Ma Padova riesce a mantenere il suo primato in campo artistico grazie a due grandi maestri: Andrea Mantegna che dipinge la Cappella Ovetari nella Chiesa degli Eremitani, andata purtroppo completamente distrutta dai bombardamenti del 1944, e Donatello, autore dello splendido monumento equestre dedicato al Gattamelata e del ciclo scultoreo costituente l'altar maggiore della Basilica del Santo.

Il Cinquecento è per la città veneta un secolo di grandi splendori. Sottoposta alla dominazione veneziana, in lotta contro il papato, l'impero e la Francia, Padova innalza un nuovo sistema di fortificazioni bastionate per un perimetro di 11 chilometri. Si tratta di un progetto di immane grandezza, realizzato febbrilmente, nato con l'obiettivo di rendere la città inespugnabile all'attacco delle artiglierie militari quali quelle della grande armata della Lega di Cambrai. Fu quello del 1509 uno dei momenti più difficili e Venezia fu ad un passo dall'essere travolta. Ma nuove guerre non si combatteranno e quelle mura, perizia dell'ingegno militare, ne determineranno il definitivo assetto urbanistico. Nel 1545 nasce l'Orto Botanico, il più antico d'Europa, istituito con precisi scopi scientifici, nel quale sono raccolte e classificate ancor oggi numerose specie di piante medicinali. Verso la fine del secolo l'università vive la stagione illuminata dal genio di Galileo Galilei ed è edificato il famoso Teatro Anatomico.

Il settecento vede la sistemazione attuale di Prato della Valle. Dopo un primo intervento di bonifica del terreno ancora in gran parte paludoso, il procuratore di Venezia, Andrea Memmo, ha in mente un progetto grandioso: un grande spazio aperto nel quale possano trovar posto le botteghe per la fiera e dove avvengano addirittura le corse dei cavalli. Ecco realizzata un'area verde, la cosiddetta isola Memmia, collegata alla piazza circostante da quattro maestosi ponti, interamente circondata da statue di uomini, soprattutto procuratori veneziani, che hanno dato il loro contributo alla storia della città

La capitolazione di Venezia, nel 1796, in seguito alla prima campagna napoleonica in Italia, conduce Padova alla dominazione francese e, poco dopo, a quella austriaca. Per lungo tempo la città è terreno di saccheggi, scorribande e devastazioni da parte degli eserciti stranieri. Unico segno positivo di quegli anni è la sistemazione della rete viaria e di alcuni importanti nodi cittadini, dovuta in gran parte all'opera dell'architetto Giuseppe Jappelli, autore del famosissimo Caffè Pedrocchi e nominato ingegnere municipale. La dominazione si conclude nel 1866 con l'annessione al Regno d'Italia.

Gli anni recenti della storia di Padova hanno conosciuto un grosso sconvolgimento del tessuto urbanistico a causa di numerose distruzioni belliche e diversi interventi di smembramento di interi quartieri per far sorgere moderni grattacieli, si pensi all'attuale piazzetta Conciapelli.

Padua between history and legend

Padua between history and legend

Padua is a city characterized by a complex town planning, that is the result of 2500 years of history, in which the city has had a leading role and it preserves some world-famous works of art: from the traces of the Roman Age splendor, to the masterpieces of the Middle Ages, as Giotto's frescos in the 'Scrovegni Chapel', the 'Palazzo della Ragione', the Basilica of S. Antonio, to the sanguinary fights between medieval soldiers, to the Venetian epic.From 1400 to the decline of the 'Serenissima', with the arrival of Napoleon, Padua is the most important city of the Venetian dry land.

The 'Dominante' leaves a really important urban mark in today's town conformation, especially thanks to the construction of the sixteenth-century walls, built to defend the city from the 'Imperiali' of the Cambrai league (this is one of the most difficult pages in the millenarian history of the Venetian Republic).

Furthermore some important buildings and palaces are built, such as Santa Giustina Basilica and the seventeenth-century arrangement of a vast, marshy area of Prato della Valle, formerly place of the Roman theatre.

Padua boasts remote origins as a fluvial town. An old legend, not scientifically confirmed, says that the city was founded by Antenore, an Homeric hero, who was escaping from Troy, committed to the flames. Archeological testimonies show the existence, approximately in the XII century b.C., of an urban settlement in a marshy area, formed because of the presence of the Brenta river, called at that time 'Medoacus'. The same place name 'Patavium', (Padua), would be referred to Padus and it would show a close relation between the Palaeo-Venetian settlement and the fluvial waters.

And still today Antenore square preserves the founder's mortal remains, near the arches of one of the Roman bridges, now covered with earth, that crossed the Naviglio inside the town: the most important waterway that joined Padua to the Lagoon.

Already in the III century B.C., thanks to its ideal position, protected by the water, Padua defeats the Galli Cisalpini and becomes a precious Roman ally. Around 50 B.C., it has its own administrative autonomy because first it acquires the Roman jus status and then the Municipium status through a Caesar decree.

The prosperity and the peace reached, permit a development of the town planning and an attempt to regulate the fluvial waters through the construction of Roman bridges. So Padua seems to be an 'island', that has natural fortifications (the river's loops), connected to the country thanks to the network of Roman roads and to the sea thanks to the shipways.

The most important Roman constructions are the theatre, that determines the today's circular conformation of 'Prato della Valle' and the amphitheatre: some traces of it are in Corso del Popolo and the Scrovegni Chapel is inside it.

Nevertheless only few architectural testimonies of this age remain because of the use to demolish the old constructions in order to obtain the stones to build the new ones. Thanks to the Roman intervention (II-I century b.C.) the town becomes one of the most important junction of the North of Italy: the Aemilia road joins Padua to Aquileia, the Aemilia-Gallica road to Vicenza and then to Genova, the Annia road to the important port of Adria.

During the first centuries of Christianity Padua is one of the most important cities of the Empire, only second to Rome in richness and beauty, but from the III-IV century it starts declining because of the frequent invasions Barbarian people: first Visigoti, Svevi and Vandali and then Unni and Longobardi. In 589 a dramatic event happens: the Brenta river, that hadn't received during the previous century any hydraulic repairs, overflows and causes a lot of terrible floods. The river deviates to the North and the Bacchiglione occupies its place.

The recovery is quite slow and difficult, only in the XII century, Padua becomes a free municipality and starts imposing its supremacy and its own cultural model to the rural area and to the near towns again. The urban-territorial recovery is possible thanks to the Benedictine monks, in fact from the VIII century, they start a widespread reclamation from Padua to the Pedemontana. Their work is the following: they find a place for a new monastery and they build it, then they build some watermills along the rivers and in this way it starts the reclamation. Thanks to the monks, there is the recovery of the 'Roman Centuriazione' (a system to divide the territory), and there is the diffusion of a new type of rural building, based on the model of the Benedictine monastery.

Around 1200, Padua finds again its economic wealth and starts a period characterized by a huge cultural fervor: there is the construction of the first medieval walls, the 'Basilica del Santo', built to house the mortal remains of Franciscan friar, now the most famous Saint in the world, and the 'Palazzo della Ragione', then there is the foundation of a prestigious University. Always in this period there are some bitter quarrels with Imperial Vicar, the terrible and ill-famed Ezzelino III da Romano, the tyrant, son-in-low of the Emperor Federico II, one of the leading figure in the medieval history.

Around 1200, Padua finds again its economic wealth and starts a period characterized by a huge cultural fervor: there is the construction of the first medieval walls, the 'Basilica del Santo', built to house the mortal remains of Franciscan friar, now the most famous Saint in the world, and the 'Palazzo della Ragione', then there is the foundation of a prestigious University. Always in this period there are some bitter quarrels with Imperial Vicar, the terrible and ill-famed Ezzelino III da Romano, the tyrant, son-in-low of the Emperor Federico II, one of the leading figure in the medieval history.The artistic scene is dominated by a prestigious figure: the Florentine Giotto, who promoted a revolution in painting. He paints in fresco the Scrovegni Chapel, one of the cornerstone of the world painting. The political power height arrives between 1338 and 1404, with the Carraresi domination. In those years also Francesco Petrarca is in Padua and he owns a house in the countryside, in Arquà, in the southern part of the Euganei hills.

In 1405 there is a lull because a popular revolution causes the passage of Padua to the Venetian Republic. But Padua maintains its artistic supremacy thanks to two big Masters: Andrea Mantegna, who paints the Ovetari Chapel in the Eremitani Church, and Donatello, who creates the equestrian monument dedicated to Gattamelata, that belongs to the sculptural cycle of the high altar in the Basilica del Santo.

The fifteenth century is characterized by a huge splendour for the Venetian town. It was under the Venetian domination, (in conflict with the Empire, the Papacy and France) that Padua erects a new system of fortifications 11 km long. It is a big project, realized feverishly, created with the objective to make the city impregnable to the attacks of the military artillery, especially that of the Cambrai League. In 1509 there is one of the most difficult moment and Venice was almost defeated. But there won't be wars anymore and those walls will be the final urban structure. In 1545 the botanical gardens are founded. They are the oldest in Europe, created to fulfill scientific purposes, in which a lot of herbs are collected and classified. At the end of the century the university has its enlightened period thanks to the genius of Galileo Galilei and it is built the famous Anatomic Theatre. It's important to remember the reconstruction, never finished, of the Basilica of Santa Giustina, on the medieval structures destroyed by an earthquake, one of the most beautiful examples of the Renaissance architectural conceptions.

In the seventeenth century there is the definitive arrangement of Prato della Valle. After a first intervention of reclamation of the marshy area, Andrea Memmo, the Venetian attorney, thinks at a grandiose project: a big open space where the shops for the fair could be placed and where there could be the horse races. So there is the realization of a green area, the so-called 'Memmia Island', joined to the square through four majestic bridges, entirely surrounded by statues, the most representing Venetian attorneys, who gave a contribute to the history of the city.

The Venetian capitulation in 1798, after the first Napoleonic campaign in Italy, leads Padua under the French domination and then under the Austrian one. The city becomes the theatre of sacks, incursions and devastations of the foreign armies. The arrangement of the road network and of some important urban junctions (thanks to the architect Giuseppe Jappelli, who created the famous 'Caffè Pedrocchi' and nominated municipal engineer) is the only positive sign of those years. The domination ends only in 1866, with the annexation to the Reign of Italy.

The recent years of the history of Padua are characterized by a big changement of the fabric of the city; because of the bellic destructions, the Eremitani Church was almost destroyed and a masterpiece of Andrea Mantegna was almost entirely lost (it is considered the biggest loss in the artistic field of the second world war), furthermore there have been some interventions to split entire quarters in order to create some space to build the modern skyscrapers (for example 'Piazzetta Conciapelli'). The city looses its features of fluvial town (as Venice, Chioggia and Treviso) because some fluvial channels were covered with earth, and Padua gives more space at the civilisation (or maybe the barbarity) of cars and of the big anonymous quarters.

| Padova, luoghi d'interesse e monumenti famosi | |

|---|---|

| luogo |  |

| piazza Municipio, palazzo del Bo, Caffè Pedrocchi | coord. N.45°24.440' E.11°52.622' |

| Piazza Erbe, Frutta, Signori e Palazzo della Ragione | coord. |

| piazza Duomo | coord. N.45°24.411' E.11°52.338' |

| piazza Basilica Sant'Antonio | coord. N.45°24.092' E.11°52.803' |

| Santa Giustina, Prato della Valle | coord. N.45°23.805' E.11°52.736' |

| Eremitani, Scrovegni | coord. |

| La Specola, Castello Carrarese | coord. N.45°24.106' E.11°52.100' |

| Mura e Porta Portello | coord. N.45°24.608' E.11°53.569' |

| Porta Trento | coord. N.45°25.025' E.11°51.957' |

| Porta Pontecorvo | coord. N.45°24.035' E.11°53.072' |

| Ospedale Civile | coord. N.45°24.203' E.11°53.290' |

| Stazione Ferroviaria | coord. N.45°24.035' E.11°52.809' |

- ascolta suono campane del Santo al mattino

- ascolta suono campane del Santo a mezzogiorno

|

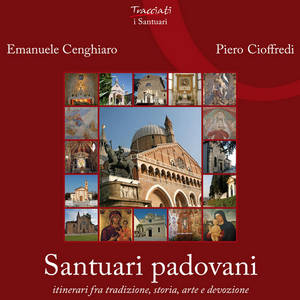

Santuari padovani.di Emanuele Cenghiaro e Piero Cioffredi |

|

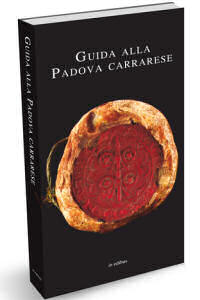

Guida alla Padova CarrareseIl 22 novembre 1405, Padova si arrese a Venezia.L’episodio segnò la fine di uno dei periodi più luminosi della storia cittadina, lungo quasi un secolo (1318-1405), durante il quale le sorti della città furono strettamente legate alle vicende della famiglia da Carrara. E proprio le figure dei Signori carraresi, impegnati a proiettare sé stessi e la città sul grande scacchiere della politica europea, costituiscono il filo conduttore di un viaggio attraverso le strade e le piazze di Padova, i suoi palazzi, le sue chiese, le sue fortificazioni. Ma non solo di monumenti tratta questa guida, ma anche dell’operosità umana, delle testimonianze materiali dalle quali traspaiono le vicende di Padova e della sua società, dei maggiorenti come del popolo, organizzato nelle fraglie professionali. Secolo veramente luminoso quello carrarese, grazie alla presenza in città di figure quali Petrarca, Guariento, Giusto de’ Menabuoi e Altichiero da Zevio. Un viaggio, dunque, attraverso i luoghi di una città europea del Trecento all’apice del suo splendore, le cui origini sono spesso ignote agli stessi padovani. ISBN 978-88-97221-02-9 AA.VV. - in edibus - 2011 - 192 pgg. con illustrazioni - 15,00 € www.edibus.it |

| bibliografia Padova e padovano | ||

|---|---|---|

| autore | titolo | edizione |

| M.B.Autizi | La Cappella degli Scrovegni - Giotto e il Cantico della Natura | 2023 - Editoriale Programma |

| Francesco Jori | Padova e i suoi Comuni | 2021 - Editoriale Proramma |

| Paolo Mameli | Ti presento Padova | 2020 - Editoriale Proramma |

| M.B e F. Autizi | Palazzo della Ragione di Padova | 2019 - Editoriale Proramma |

| Remy Simonetti | Il dominio del Carro | 2013 - In Edibus Edizioni |

| Ugo Fadini | Mura di Padova - Guida al sistema bastionato rinascimentale | 2013 - In Edibus Edizioni |

| autori vari | Guida alla città di Padova | 2013 - Storti Edizioni |

| P.Cioffredi, E.Cenghiaro | Santuari padovani. Itinerari fra tradizione, storia, arte e devozione | 2013 - Tracciati Padova |

| autori vari | Vita di Sant'Antonio | 2012 - Storti Edizioni |

| G.Perbellini, F.Rodeghiero | Città murate del Veneto | 2011 - Cierre Edizioni |

| Francesco Businaro | Guida alla Padova Carrarese | 2011 - In Edibus Edizioni |

| R.Simonetti | Da Padova a Venezia nel medioevo. Terre mobili, confini, conflitti | 2009 |

| Emanuele Chenghiaro | Padova al di là delle mura | 2007 - Tracciati Padova |

| Oddone Longo e autori vari | Padua felix - Storie padovane illustri | 2007 - Esedra Padova |

| D.Banzato, F.D'Arcais | I luoghi dei Carraresi | 2006 |

| Oddone Longo | Padova Carrarese | 2005 |

| G.Beltrame | Appunti di storia padovana | 2000 |

| F.Randi, L.Tramarollo | Padova, una città per i ragazzi | 1998 - Marcato Padova |

| M.Bonarrigo | Padova: la città, le acque | 1992 - Abano Terme |

| Raffaele Mambella | Padova e il suo territorio nell'antichità | 1991 - Libreria Zielo, Este |

| Gigi Vasoin | La signoria dei Carraresi nella Padova del '300 | 1987 - La Garangola Padova |

| S.Ghironi | Padova, piante e vedute, 1449-1865 | 1985 - Padova |

| L.Puppi, G.Toffanin | Guida di Padova. Arte e storia tra vie e piazze | 1983 - Trieste |

| Elio Franzin | Padova e le sue mura | 1982 - Signum Padova |

| autori vari | Padova, il caso mura medioevali | 1981 - Padova |

| L.Puppi | Padova, Basiliche e Chiese | 1975 - Vicenza |

| P.Giulini, R.Casagrande | Verde e mura a Padova: una difficile coabitazione | 1981 - Padova |

| Lionello Puppi | Prato della Valle: due millenni di storia di un'avventura urbana | 1986 - Padova |

| G.Lorenzoni | Gli ordini mendicanti e la città di Padova nei secoli XIII e XIV | 1985 - Padova |

| L.Capuis, S.Pesavento | Padova: dalla città paleoveneta alla città romana | 1985 - Padova |

| Giulio Bresciani Alvarez | Struttura e segno: elementi per una lettura architettonica-urbanistica nel centro storico di Padova | 1985 - Padova |

| L.Tomasin | Testi padovani del Trecento | Esedra Editrice |

| Pier Vincenzo Mengaldo | Studi su Ippolito Nievo | Esedra Editrice |

| A.Verdi | Il sistema bastionato di Padova: analisi morfologica | 1986 - Padova |

| G.Toffanin | Padova tra ottocento e novecento | 1982 - Milano |

| A.Calore | Case medioevali padovane e barbacani | 1974 - Museo Civico Padova |

| E.Bressan | Il Castello di Padova. Storia e vicende del castello di Padova dalle origini ai giorni nostri | 1986 - Treviso |

| La distruzione di Padova al tempo di Re Agilulfo | D.Gallo | 1985 - Erredieci |

| G.Cappelletti | Storia di Padova dalla sua origine sino al presente | 1875 - Padova |

| Andrea Gloria | Il territorio padovano illustrato (4 vol.) | 1862 - Padova |

| Ottone Brentari | Guida di Padova | 1891 - Padova |

| Pietro Selvatico | Guida di Padova e dei suoi principali contorni | 1869 - Padova |

| L.Formentoni | Passeggiate storiche per la città di Padova | 1880 - Padova |

| F.Cessi, L.Gaudenzio | Padova attraverso i secoli | 1958 - Padova |

| M.Checchi, L.Gaudenzio, L.Grossato | Padova. Guida ai monumenti e alle opere d'arte | 1961 - Venezia |

| L.Braccesi | La leggenda di Antenore | Saggi Marsilio, Padova |

| Este preromana: una città e i suoi santuari - Este Veneta | Canova Edizioni | |

| Historia de urbiis patavii antiquitate | Bernardino Scardeone | 1560 |